How Do You Measure Microplastics In Animals

People around the world discard tons of tiny bits of plastic every twelvemonth. Those bits can break downwardly into pieces no bigger than a sesame seed or slice of lint. Much of that waste matter eventually volition wind up loose in the surround. These microplastics have been establish throughout the oceans and locked in Arctic ice. They tin can terminate upwardly in the food concatenation, showing upward in animals large and modest. Now a host of new studies show that microplastics tin break down rapidly. And in some cases, they tin can alter unabridged ecosystems.

Scientists take been finding these plastic bits in all kinds of animals, from tiny crustaceans to birds and whales. Their size is a concern. Small animals depression on the food concatenation eat them. When larger animals feed on the small animals, they tin can finish upward also consuming large amounts of plastic.

And that plastic tin can exist toxic.

Nashami Alnajar is part of a team at the University of Plymouth in England that has just examined the result of microfibers on marine mussels. Animals exposed to plastic-tainted dryer lint had broken DNA. They also had deformed gills and digestive tubes. The researchers say that it'due south not articulate the plastic fibers caused these problems. Zinc and other minerals leached out of the microfibers. And these minerals, they now contend, likely damaged the mussels' cells.

Mussels aren't the only animals that consume plastic. And often not on purpose. Consider Northern fulmars. These seabirds eat fish, squid and jellyfish. As they scoop their prey from the water's surface they may pick up some plastic, likewise. In fact, some plastic bags look like food — but aren't.

The birds fly long distances in search of a meal. To survive those long treks, a fulmar stores oil from recent meals in its stomach. This oil is lightweight and free energy rich. That makes it a quick source of fuel for the bird.

Some plastics incorporate additives, chemicals that give them features that help that last longer or function better. Some plastic chemicals dissolve in oils. Susanne Kühn wanted to know if those additives might end up in the birds' stomach oil. Kühn is a marine biologist at Wageningen Marine Research in holland. Might these chemicals seep into the breadbasket oil of a fulmar?

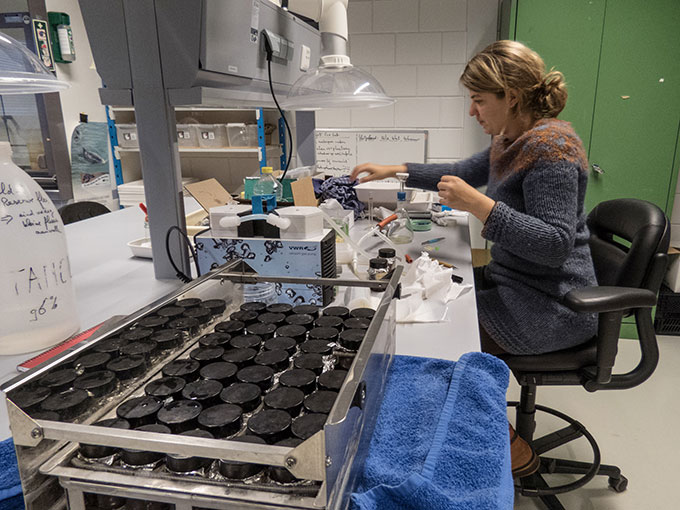

To find out, she teamed up with other researchers in the Netherlands, Norway and Federal republic of germany. They gathered different types of plastic from beaches and crushed information technology into microplastics. The researchers then extracted tummy oil from fulmars. They pooled the oils and poured it into drinking glass jars.

They left some jars solitary. In others, they added the microplastics. The researchers and so placed the jars in a warm bathroom to mimic the temperatures within a bird'southward stomach. Again and again over hours, days, weeks and months, they tested the oils, looking for the plastic'south additives.

And they found them. A diversity of these additives leached into the oil. They included resins, flame retardants, chemical stabilizers and more. Many of these chemicals are known to impairment reproduction in birds and fish. Nearly entered the tum oil quickly.

Her team described its findings August xix in Frontiers in Ecology Science.

Kühn was surprised that "inside hours, plastic additives can leach from plastic to fulmars." She likewise hadn't expected so many chemicals to enter the oil. The birds may betrayal themselves to these additives once again and once more, she says. A bird's muscular gizzard grinds up the bones and other hard bits of its prey. It too can grind up plastic, she notes. That could expose even more than plastic to the birds' breadbasket oil.

Smaller pieces, bigger bug

Every bit plastic pieces pause downwards, the total surface area of the plastic increases. This larger surface area allows for more interactions between the plastic and its surroundings.

Until recently, scientists idea sunlight or crashing waves were needed to intermission plastics downwardly. Such processes could take years to release microplastics into the surroundings.

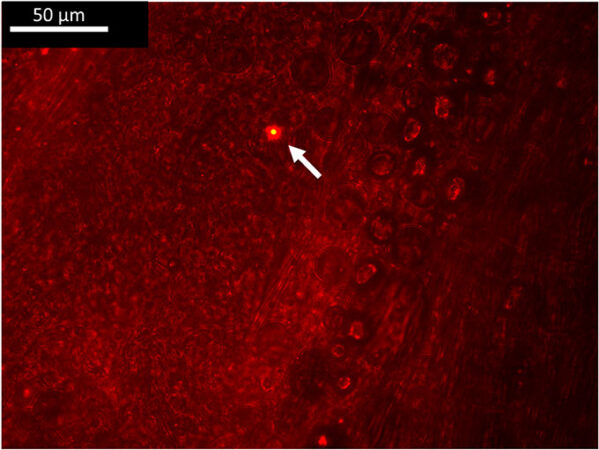

But a 2018 study discovered that animals play a role as well. The researchers institute that Antarctic krill can pulverize microplastics. These small body of water-dwelling crustaceans intermission microplastics downward into fifty-fifty smaller nanoplastics. Nanoplastics are so tiny they can go inside cells. Terminal year, researchers at the University of Bonn, Federal republic of germany, showed that once there, those nanoplastics tin can damage proteins.

Microplastics are mutual in streams and rivers, also. Alicia Mateos-Cárdenas wanted to know if freshwater crustaceans besides break down microplastics. She'south an environmental scientists who studies plastic pollution at University College Cork in Ireland. She and her colleagues collected shrimp-like amphipods from a nearby stream. These critters have toothed mouthparts to grind up food. Mateos-Cárdenas thought they might likewise grind plastic.

To exam this, her team added microplastics to beakers containing amphipods. After 4 days, they filtered pieces of that plastic from the water and examined them. They likewise checked each amphipod's gut, looking for swallowed plastic.

In fact, most half the amphipods had plastic in their guts. What's more, they had turned some microplastics into tiny nanoplastics. And it took simply four days. That'southward a serious business organization, Mateos-Cárdenas now says. Why? "Information technology is believed that the negative impacts of plastics increment as particle size decreases," she explains.

Exactly how those nanoplastics could touch an organism remains unknown. Simply these chopped up nanobits will likely movement through the environment once created. "Amphipods did not defecate them, at least not during the length of our experiments," Mateos-Cárdenas reports. Only that doesn't mean nanoplastics stay in the amphipod's gut. "Amphipods are prey for other species," she says. "So they can be passing these fragments through the nutrient concatenation" to their predators.

Not just a h2o problem

Much of the inquiry on microplastics has focused on rivers, lakes and oceans. But plastics are a major trouble on state, too. From water bottles and grocery bags to auto tires, discarded plastics pollute soils around the globe.

Dunmei Lin and Nicolas Fanin were curious how microplastics might affect soil organisms. Lin is an ecologist at Chongqing University in Mainland china. Fanin is an ecologist at France's National Research Institute for Agriculture, Nutrient and Environment, or INRAE. Created in January 2020, information technology's in Villenave-d'Ornon. Soils teem with microscopic life. Bacteria, fungi and other tiny organisms thrive in the stuff nosotros call dirt. Those microscopic communities involve food-web interactions like those visible in larger ecosystems.

Lin and Fanin decided to mark off plots of woods soil. After mixing up the soil at each site, they added microplastics to some of those plots.

More than than nine months later, the team analyzed samples collected from the plots. They identified lots of larger organisms. These included ants, wing and moth larvae, mites and more. They as well examined microscopic worms, chosen nematodes. And they didn't overlook soil microbes (bacteria and fungi) and their enzymes. Those enzymes are one sign of how active the microbes were. The team and so compared their analysis of the plots with microplastics to soils without the plastic.

The microbial communities didn't seem much affected by the plastic. At least not in terms of sheer numbers. But where plastics were present, some microbes ramped up their enzymes. That was especially true for enzymes involved in the microbes' use of important nutrients, such as carbon, nitrogen, or phosphorous. Microplastics may accept changed the available nutrients, Fanin at present concludes. And those changes may accept altered the enzyme activity of the microbes.

Larger organisms fare even less well with the microplastics, the report showed. Nematodes that swallow leaner and fungi were fine, perhaps because their prey was non afflicted. All other types of nematodes, yet, became less mutual in the plastic-tainted soil. And so did mites. Both animals play a role in decomposition. Losing them could have major impacts on the woods ecosystem. Numbers of the larger organisms, such as ants and larvae, likewise decreased. It's possible the plastic poisoned them. Or they might simply have moved to less polluted soils.

These new studies "continue to demonstrate that microplastics are everywhere," says Imari Walker Karega. She is a plastic-pollution researcher at Duke University in Durham, Due north.C. Each study leads to new questions requiring additional research, she says. Merely even now, she says, information technology's articulate that microplastics tin can have an impact on ecosystems everywhere. That includes our food crops, she says.

"I believe that anybody, regardless of their age, tin tackle the result with plastic pollution by making better choices," says Mateos-Cárdenas. "Nosotros need to take care of [the planet] for our future selves and everyone who is coming later u.s.."

Source: https://www.sciencenewsforstudents.org/article/polluting-microplastics-harm-both-animals-and-ecosystems

Posted by: brubakergoour1986.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How Do You Measure Microplastics In Animals"

Post a Comment